Introduction

The China-Australia trade relationship is one of the most economically complementary—and complex—partnerships in the world. It is defined by scale, necessity, and resilience. For Australia, China is the undisputed heavyweight champion of commerce, accounting for nearly one-third of its total trade with the world [Source: DFAT]. For China, Australia is not just a market, but a strategic “quarry” and “farm” that fuels its massive industrial engine and, increasingly, its green energy transition.

This blog explores the full arc of this vital economic corridor. We move beyond the headlines to analyze the mechanics of the relationship—from its desperate historical roots in the 1960s to the high-tech exchange of critical minerals and electric vehicles in 2026. Putting political narratives aside, we focus here strictly on the commerce, the supply chains, and the economic realities that bind these two nations together.

1. A Historical Foundation: From Tea to Wheat

The China – Australia is far older than the modern diplomatic era. It began not with iron ore, but with tea and gold, and was cemented during a moment of humanitarian crisis.

The Gold Rush Era (1850s): The first significant wave of commerce occurred during the Victorian gold rushes of the 1850s, which attracted over 40,000 Chinese prospectors to Australian shores. This era established the first viable supply routes, with Australia importing tea, rice, and silk from China while exporting gold. By 1856, goods from China accounted for 3.3% of all imports into Victoria, creating a commercial familiarity that predated the Federation of Australia [Source: NMA].

The Wheat Breakthrough (1960s): A pivotal, often overlooked moment occurred in the early 1960s. During the Great Famine, China faced a desperate food shortage. Despite the intense geopolitical tensions of the Cold War and the lack of formal diplomatic recognition, the Australian Wheat Board made the pragmatic decision to export wheat to China on credit.

- The Numbers: In 1961 alone, Australia exported over 2 million tonnes of wheat to China.

- The Impact: By the mid-1960s, roughly 40% of Australia’s wheat crop was being shipped to China, effectively saving the Australian wheat industry from a global glut while providing a lifeline to Beijing. This “wheat diplomacy” established a reputation for Australia as a reliable food security partner, a reputation that paved the way for formal diplomatic recognition in 1972 [Source: National Archives of Australia].

The Resources Boom (2000s): As China’s economy liberalized and urbanization accelerated in the 21st century, its demand for steel sky-rocketed. Australia, with its vast, accessible reserves of iron ore and coking coal, became the natural supplier. This period marked the “mining boom,” cementing the economic interdependence we see today. Between 2005 and 2015, the value of Australian exports to China grew at an average annual rate of nearly 20%.

2. The ChAFTA Era: A Decade of Integration

December 2025 marked the 10th anniversary of the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA), a landmark deal that entered into force in late 2015. While political relations have fluctuated, the ChAFTA framework has remained the bedrock of China-Australia trade stability.

Tariff Elimination Mechanics: ChAFTA was designed to be progressive. Over the last decade, we have seen the systematic dismantling of barriers:

- Dairy: Tariffs on Australian dairy products (which ranged up to 20%) were completely phased out by January 1, 2026. This has allowed Australian milk powder and fresh milk to compete directly with New Zealand products on supermarket shelves in Shanghai.

- Wine: Prior to the agreement, Australian wine faced tariffs of 14-20%. These were eliminated by 2019, fueling a “golden age” of wine exports that reached $1.2 billion annually before the 2020 disruptions.

- Seafood: Tariffs on rock lobster and abalone—delicacies in Chinese banquet culture—dropped to zero, giving Australian exporters a 10-15% price advantage over competitors from non-FTA nations.

Service Sector Growth: The agreement was not just about goods; it opened doors for Australian service providers. It granted Australian law firms easier access to establish offices in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone and allowed Australian private hospitals to establish wholly-owned subsidiaries in China—a privilege granted to very few nations [Source: Austrade].

3. The Present Landscape: Iron Ore, EVs, and the Safeguard Mechanism

As of early 2026, China-Australia trade has evolved into a sophisticated two-way street. The dynamic is no longer just “Australia digs, China manufactures.” It is becoming a cycle of high-tech manufacturing and strategic resource management.

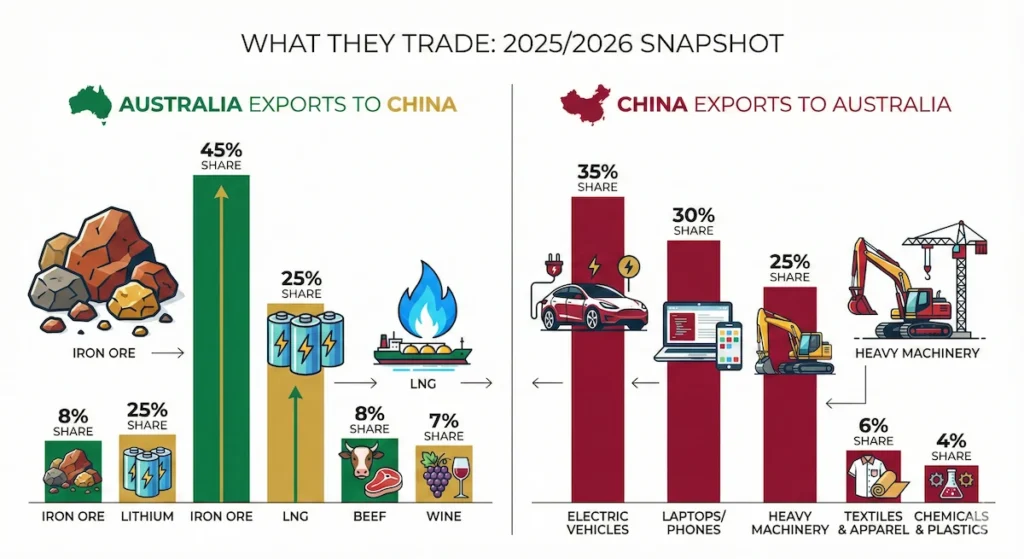

The Export Mix (Australia to China): Australia’s exports are still dominated by resources, but the composition is shifting and the rules are tightening.

- Iron Ore: This remains the heavyweight champion, accounting for nearly 60% of Australia’s exports to China by value. Despite China’s push to diversify supply (developing the Simandou mine in Guinea), Australian ore remains the baseline feedstock for Chinese steel mills due to its high quality and proximity.

- Agriculture & The Safeguard Mechanism: While trade is flowing, it is regulated by strict mechanisms. A prime example is the Beef Safeguard. As of January 1, 2026, China implemented a safeguard tariff on beef imports from multiple nations, including Australia. This mechanism—part of the original ChAFTA text—allows China to reimpose tariffs if import volumes exceed a set annual quota. With Australian beef exports surging in late 2025 due to herd rebuilding, this “snapback” tariff serves as a reminder that volume safeguards are a standard, albeit painful, part of trade mechanics intended to protect domestic Chinese producers [Source: Global Times].

The Import Mix (China to Australia): Australia is increasingly running on Chinese technology.

- Electric Vehicles (EVs): China is now the primary source of EVs for the Australian market.

- Market Share: By the end of 2025, Chinese-made vehicles (including Western brands like Tesla manufactured in Shanghai, and domestic giants like BYD and MG) accounted for over 80% of EV sales in Australia.

- The BYD Phenomenon: The BYD Atto 3 and the MG4 have democratized access to green transport, offering price points under AUD $40,000 that Western manufacturers have struggled to match.

- Telecommunications & Tech: From the 5G modules in industrial routers to the laptops used in Australian schools, Chinese manufacturing supplies the digital backbone of Australian daily life [Source: OEC].

4. Future Possibilities: The Green Energy Pivot

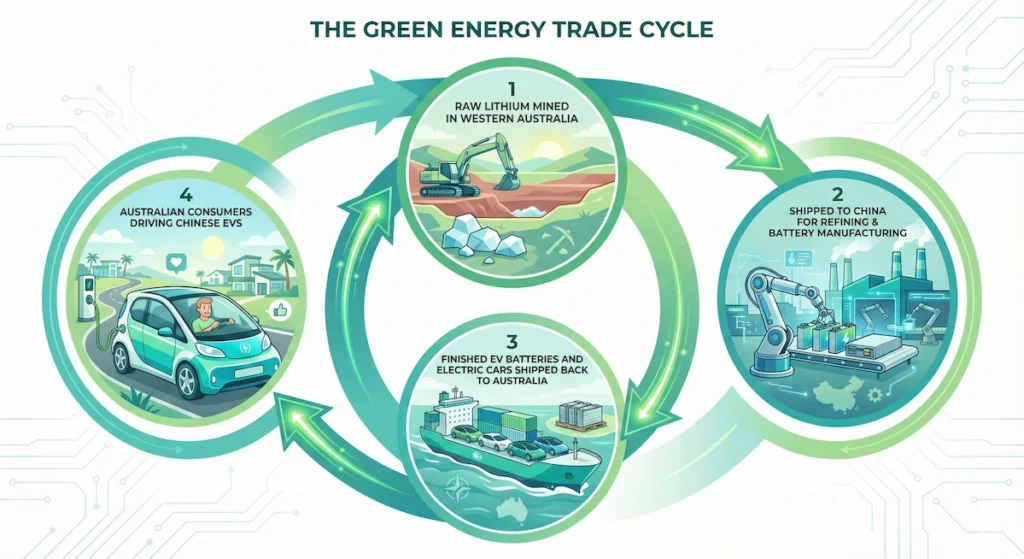

The future of China-Australia trade lies in the Green Transition. Both nations are locking into a new form of interdependence centered on decarbonization. While politicians talk of “de-risking,” the commercial reality is one of “green entanglement.”

A. The Lithium Link: A Symbiotic Stranglehold Australia produces over 50% of the world’s raw lithium (spodumene), but China controls approximately 60% of the global refining capacity that turns that rock into battery-grade chemicals. This has created a symbiotic link that neither nation can easily break.

- The 94% Reality: In 2025, a staggering 94% of Australia’s spodumene exports were shipped to China for processing.

- Corporate Integration: This trade is cemented by joint ventures. Australia’s largest lithium mine, Greenbushes in Western Australia, is operated by a joint venture between Tianqi Lithium (China) and IGO (Australia), alongside US giant Albemarle. This structure ensures that despite geopolitical noise, the supply chain remains integrated at the boardroom level.

- Resilience: When lithium prices corrected in late 2025, volume remained high, proving that Chinese refiners and Australian miners are locked into a long-term volume strategy [Source: IGO Ltd].

B. Green Hydrogen & The “Green Iron” Dream As China’s steel industry faces immense pressure to decarbonize, the traditional iron ore trade is looking for an upgrade. The “Holy Grail” is shifting from exporting raw iron ore (which requires dirty coking coal to smelt) to exporting “Green Iron”—ore processed in Australia using renewable hydrogen.

- Tangible Projects: Progress is visible in projects like the Murchison Green Hydrogen Project. With a Final Investment Decision (FID) targeted for late 2026, this massive 6GW facility aims to export green ammonia to hungry Asian markets. China, as the world’s largest hydrogen consumer, is a prime potential market for this clean fuel [Source: Austrade].

C. Solar Synergies While solar manufacturing is dominated by China, the intellectual property (IP) often starts in Australia. The “PERC” solar cell technology, which dominates the global market, was pioneered at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). This “brain-to-factory” pipeline remains active, with Australian researchers and Chinese manufacturers like Longi continuing to collaborate on next-generation efficiency improvements.

5. The Services Renaissance

Finally, we cannot ignore the “people-to-people” trade, which is staging a massive comeback.

Education as an Export: International education is Australia’s largest service export, and Chinese students are the cornerstone of this sector. After the disruptions of the pandemic and the diversification drives of 2022-2024, 2025 saw a stabilization of numbers.

- Economic Contribution: In 2024, education-related travel exports to China were valued at approximately AUD $12.7 billion [Source: Department of Education].

- The Shift: The market has matured. It is no longer just about undergraduate business degrees; there is a surge in Chinese students pursuing post-graduate research in renewable energy, engineering, and biotechnology, mirroring the strategic shifts in the broader economy.

Tourism Recovery: With flight capacity returning to 100% of pre-pandemic levels by late 2025, Chinese tourism has rebounded. However, the nature of the tourist has changed. We are seeing fewer large tour groups and more “Free Independent Travelers” (FITs) who stay longer, spend more, and venture into regional Australia, distributing the economic benefits beyond Sydney and Melbourne.

Conclusion

The trade relationship between China and Australia is a testament to economic gravity. Despite differing political systems and regulatory hurdles like the 2026 beef safeguard, the commercial logic of their partnership is undeniable. Australia has the resources (lithium, iron, food) and energy; China has the industrial capacity (batteries, EVs, steel) and the consumer market.

As both nations pivot toward a low-carbon future, this trading lane is set to become not just busier, but smarter. The “dig and ship” model of the 20th century is being replaced by a sophisticated integration of green supply chains, where Australian rocks and Chinese refining combine to power the global energy transition.